It is tempting to think that new, digital media should be able to recapture every element of the old and to show them in a new light. This begs the question of how far have online tools come along in making that a reality to the potential benefit of historians.

This week, I tried multiple online databases and tools–Google Books and Google’s N-Gram Viewer, Voyant Tools, and HathiTrust’s Bookworm–to analyze the language of a text–in this case, a chapter in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

Google Books

First, Google Books. The digital “preview” of the book was mostly consistent with the original text, with the only exception being a missing illustration. When I converted this digital image on Google Books into plain text, however, more inconsistencies appeared.

In addition to the aforementioned illustration, the plain text omitted the use of larger letters to indicate new paragraphs, misconstrued seemingly random marks above letters in the digital images as apostrophe marks and made minor (though noticeable) typos.

While these mistakes seem superficial, they can add up if one were to try to repeat this process for multiple texts. If unresolved, such errors can limit the twin goals of making old texts both accessible and readable on a platform such as this.

Voyant

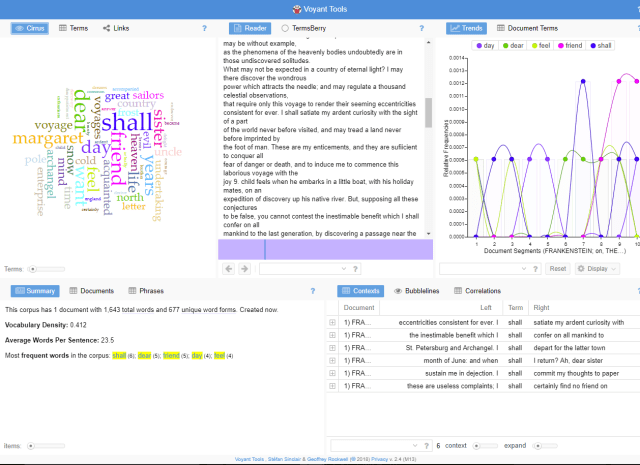

Sites like Voyant Tools, on the other hand, seem to bear potential for helping historians measure the presence and spread of ideas and key language within a source.

For instance, upon analyzing the text in the first chapter of Frankenstein, Voyant Tools calculated that Mary Shelley most frequently used words such as “voyage”, “dear,” and “fear,” and presented that information in the form of a word cloud, a chart, and other forms.

From the data provided by Valiant, we could derive that the text involves personal relationships with family, travel and both faith and uncertainty on the part of the character. In conjunction with reading the text, this analysis provided by Valiant could make it easier for readers to identify themes in writing, if not patterns in the writer’s choice of words and, in doing so, be better able to identify what cultural or periodic influences influenced the creation of written work.

NGram and Bookworm

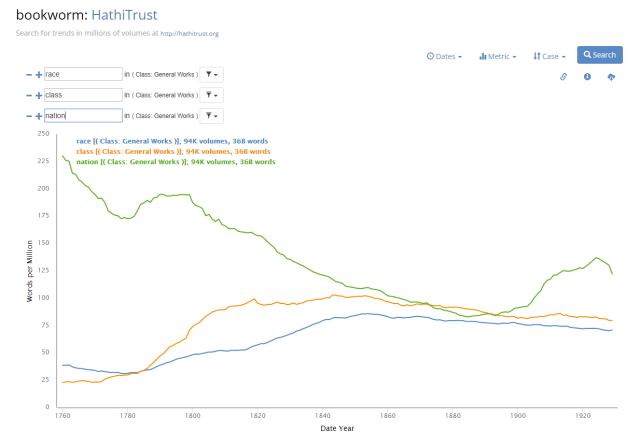

To further that goal, Google’s N-Gram Viewer and HathiTrust’s Bookworm app allows users to quantify and graph the frequency in use of language between texts across centuries.

Using Google’s N-Gram viewer, users could, for instance, illustrate the uses of words such as “race,” “class,” or nation within a chosen timeline. The viewer also lets users take advantage of Google Books database by allowing them to see lists of texts using their targeted language in specific time spans by clicking on time-ranges just beneath the graph.

Searching by the language of the text presents a particular use to historians interested in tracing the influence of ideas over time. Tracing the use of “nation” or “race” in Germany from 1800 to the mid-1960’s, for instance, creates a graph that indicates a peak in these terms’ prolificacy among texts in the mid-1930’s. Utilizing this knowledge, historians could better identify times when ideas gained greater cultural currency across cultures and posit theories regarding the reason why (in this case, potentially the rise of Fascism and ideas of racial science in Germany).

Bookworm operates in a similar way, but with greater limits and some hangups in its interface. While this app also graphs the frequency of language over time, the database of books it draws from is limited to older texts beyond copyright. Furthermore, to view texts from a historic period, users have to click on the exact part of the timeline on the graph to open a popup menu, which seems slow to respond at the time of writing.

In sum, the many online tools for textual analysis offered by Google and its peers do hold out promise for historians trying to trace the influence of ideas over time. As a historian, I have to contend with categories and rhetoric around class, race, empire, or the idea of the nation quite often. Having tried each of the different sites I have mentioned, I can safely say this level of textual analysis could assist people in my field to find at what time key terms familiar to us in the present became part of the written language of a society.

Though more steps ought to be taken to make these apps more user-friendly and the translation of analog text to digital form more accurate, textual analysis sites and apps should not be ignored as a potential tool in the historian’s ever-growing toolbelt.